Since moving to Inwood I’d heard stories of an almost mythical figure known only as Princess Naomi, who, in the 1930’s, took up residence near the old tulip tree in Inwood Hill Park. The site of the tree, which was felled by a hurricane in 1938, is now marked by a boulder with a plaque claiming to be the spot where Native Americans sold the entire island of Manhattan for a handful of trinkets. But for years, or so I’d been told, the shady spot along the Spuyten Duyvil, belonged to Naomi.

The story of Naomi fascinated me and I decided to make a trip to the National Museum of the American Indian to make an inquiry. What I received was an earful and an education on the public’s romantic notion of Indian life as presented in both history books and popular culture. “First of all,” I was told, “there is no such thing as an Indian Princess.”

“Have you ever heard of an Indian King or Queen or Duke?” the woman asked in an unabashedly mocking tone.

“No,” I apologized, not meaning to offend.

Soon a rational discussion began, but the helpful staff of librarians and historians could find no mention of Naomi, sometimes spelled Naomie, in their records.

So the hunt continued—but gradually I began to stumble on bits and pieces of Naomi’s life and times in Inwood Hill.

Her real name was Naomi Kennedy. She hailed from New Orleans. And, if the stories are to be believed, she was of Cherokee descent. (The original inhabitants of the area had been the Lenape.)

According to a 1935 column in the New York Evening Post, titled “A Good Time on a Quarter,” tourists, curious New Yorkers and children could take the subway to 207th Street and “lunch with an Indian with a gold tooth.”

The Indian, of course, was Naomi.

According to the article, in order to reach Naomi, one had to “walk west into Inwood Hill Park and take the plainly marked trail to the Tulip tree where Hendrick Hudson stepped ashore to barter with the Indians.”

And while the writer of the Post article, one Henry Beckett, may not have had a full grasp of Hudson’s voyage nor the politically correct vernacular of the modern age, he had met Naomi under the tulip tree in 1935 and left behind a description for the ages.

According to Beckett, “Just beyond the tree, now dying at last, is a small brown house with green shutters. Go around to the front porch. Unless unlucky, Indian braves and squaws in rocking chairs making souvenir trinkets of bright beads. Speak boldly, for there’s not a tomahawk on the premises, and ask for Princess Naomi.”

“Okay friend,” she said, using the Cherokee word for “righto,” when I requested a pow-wow. “Step inside and have a chair while I get my specs.”

Although her skin is coppery, the princess has a smile that is literally golden because of a gold tooth. She wears Indian clothes decorated with much beadwork.

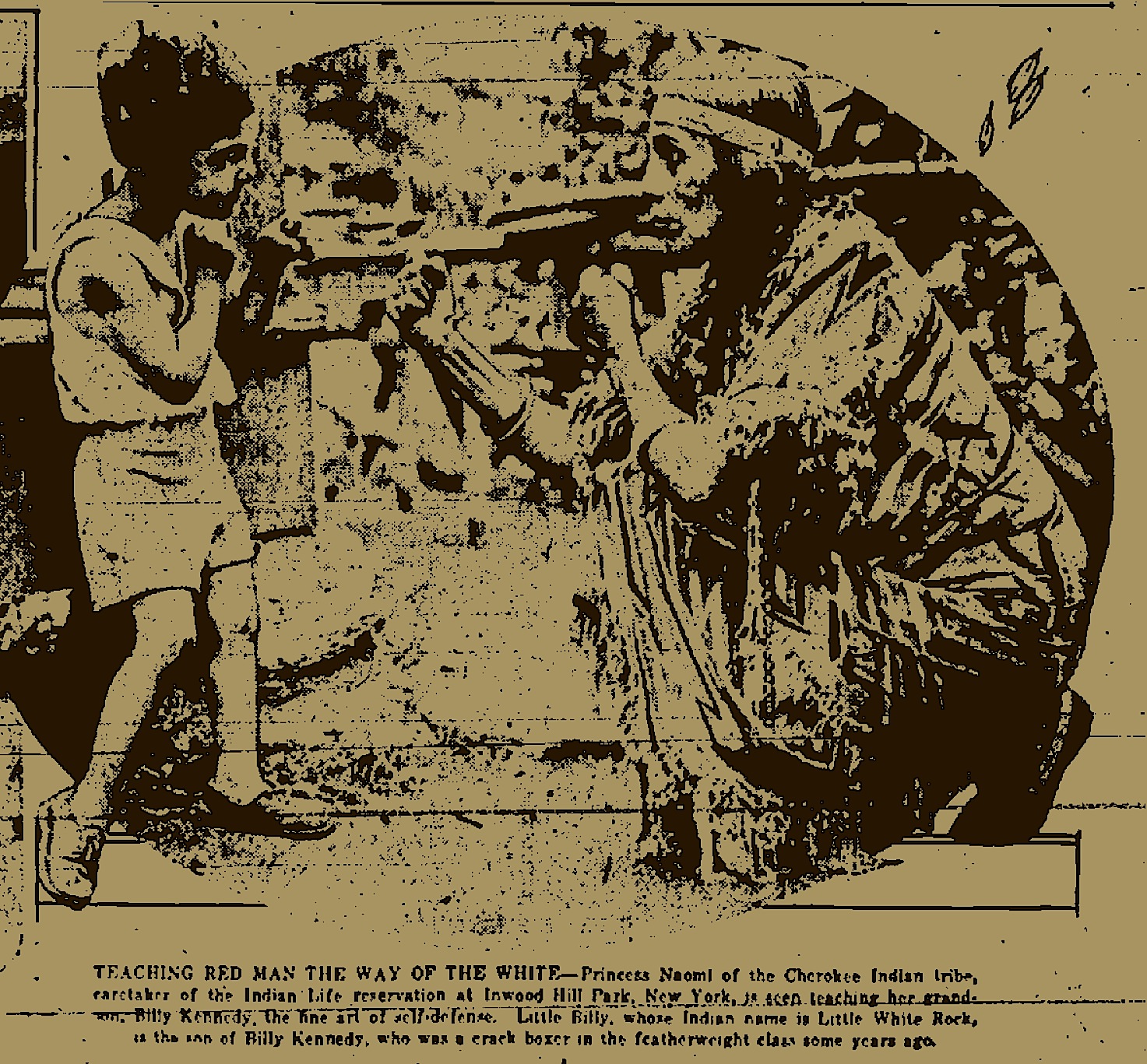

“Cherokees,” she said, “don’t have much show around here, so I am lucky to have this place. I come from Oklahoma and my tribe used to live in Georgia, where they learned to speak English. Well, I always wanted to come to New York, but my son, a boxer—he goes by the name of Billy Kennedy—told me I couldn’t stand an ordinary house, with steam heat, so he put in an application to get me the post of caretaker here.”

Thus it happens that a Cherokee princess is now queen of the Vale of Shora-Kap-Pok, a glen where the Weckuaesgeek once lived.

Naomi then went on to tell the reporter that she had held the post for the past six years.

“I must be the goods,” Naomi said.

“All of the Indians in the city, about 600 of them, members of fifty tribes, come to see me. Some make baskets, bracelets, and moccasins. Those on the porch now are Iroquois. I get along with them all—Algonquians, Mohawk, anything. I’m vice-president of the United Indians of America, a Brooklyn organization. September 29 is Indian Day up here. Big Doings.”

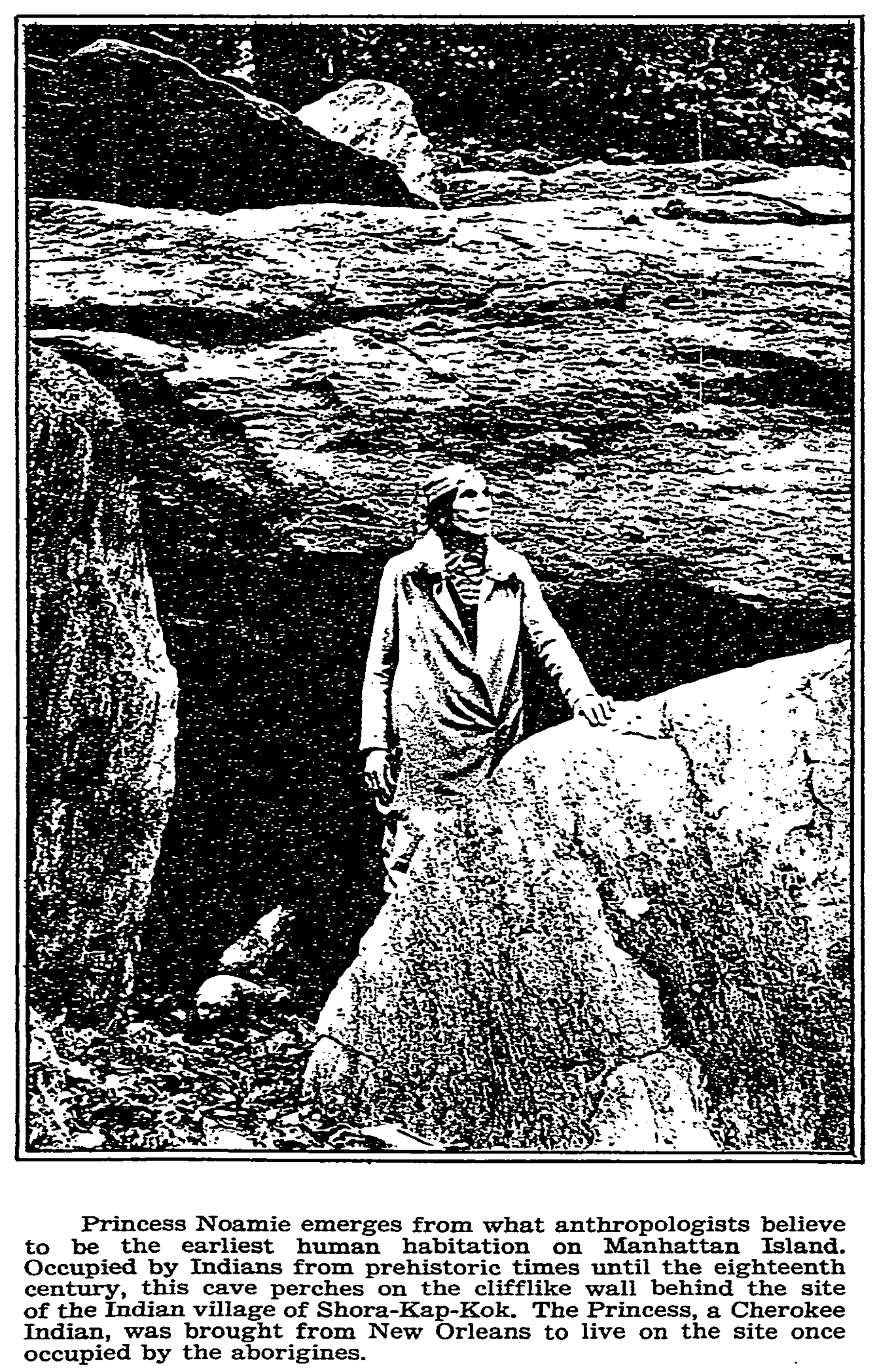

Naomi went on to tell the reporter, “Back in the woods a bit is what’s called an Indian cave, but between you and I and the gate-post, I don’t believe Indians ever lived there. It leaks. Oh, here comes Chief White Eagle. My tribalman.”

“The chief,” the article continues, “who lives at the Y.M.C.A. and is a CWA recreation leader, wants to establish a real Indian village, with tepees and more substantial houses, all in Indian style.”

Interviewing Chief White Eagle, the reporter learned more of the plan for an Indian village in the park: “Indians would come here from all over. Railroads could advertise it. Grand publicity. I have a general plan for the village, but in order to lay it out right I must first fly over the ground in an airplane.”

Following up on Chief White Eagle’s comment, the reporter wrote: “The Chief’s countenance was as solemn as a Chief’s face should be. If the idea of using an airplane to lay out an Indian village struck him as incongruous, he did not show it.”

In summary, the Post reporter wrote, “The attractions of Inwood Park include glacial pot holes, with boulders maybe 50,000 years old, a shell heap indicating hundreds of years of Indian feasting, the pottery studio of Harry and Aimee Voorhees and the Dyckman Institute with its collections.

You too dear reader can lunch with an Indian princess on the shore of the Spuyten Duyvil (Harlem Ship Canal to you). Bring your own lunch.

EXPENSES: Subway: 10 cents. Large root beer served by princess: 10 cents. Bead trinket: nickel. Total: Two bits.

But Princess Naomi was much more than a local curiosity. She was part of a growing neighborhood of which she truly seemed to care about.

Several years before the article in the Post, Naomi saw a group of nearly thirty Inwood kids sliding and playing on the then frozen Spuyten Duyvil. According to a 1932 article in the Niagara Falls Gazette, Naomi warned the children that the ice was dangerously thin; but kids being kids, they failed to heed her warning.

A short time later the ice gave way.

Naomi and her son Bill were helpless to stop the unfolding tragedy as they watched the kids take the icy plunge from the window of their cottage.

As the wet and shivering children scrambled out of the Spuyten Duyvil many likely made their way to Naomi’s cottage, described as a wooden shack directly across from the old Isham Park Yacht Club.

Unfortunately one child, ten-year-old James “Red” McGuire, who lived on Cooper street and attended Good Shepherd, drowned in the tragedy.

Of course there are other sources that mention Princess Naomi including the oral histories collected by author Jeff Kisseloff in his book “You Must Remember This.”

In one section Kisseloff interviews Dorothy Menkin who moved to Inwood from the Bronx in 1933. In the book Menkin describes the Inwood Hill Park of her youth: “There were two peach trees at the very top overlooking Dyckman Street. The kids used to eat them, and of course they got sick. Then there was the famous tulip tree. It was almost dead then. They were propping it up with cement. The Indians would come in September and dance around that tree and sing their songs. Princess Naomi had her little gift shop next to the tree. She was some character. She was in costume all the time, but come Sunday she took the costume off and walked around 207th Street with high heels and everything.”

Another former Inwood resident, Mary Devlin, who was born in 1900, also had fond memories of Princess Naomi. From her description to Jeff Kisseloff: “I used to take my children up to Inwood Hill Park every day. There was a big spring right by Princess Naomi’s shop. I would bring my empty milk bottles, fill them with water, and bring them home.

Princess Naomi was lovely. My children were crazy about her. She had a little museum with trinkets and things. On Labor Day weekend, they had pow-wows every year. The Indians came from all over, and they pitched their tents. Then the men would put up a platform, where they all did their dances, and they had Indian contests.”

But while these staged gatherings were thrilling events for the children of Inwood and the surrounding region, the participants themselves often had misgivings about the performances.

Native American Gloria Miguel, who lived in Brooklyn, dreaded the subway rides to Inwood. Half Algonquin and half Cuna (a Central American tribe), young Gloria, who answered to Bright Moon at home, described her childhood experiences to Jeff Kisseloff:

“When I went up to Inwood, it was like a big spotlight on me. I went along with my family because they took me, but I was very shy about it. I didn’t want people to look at me or take photographs of me. It wasn’t until later that I realized that my background was something to be very proud of and that those people were just ignorant.

I had a North American outfit that my mother made for me. It was a little dress made of cloth with some fringe on it. I had moccasins and a beaded headband. It was just a show outfit. It wasn’t from the background of my people. Since my parents did this for show business, they dressed according to what the show was. They both had authentic costumes at home. I just sat in my costume and watched.

Indian festival day in Inwood Hill Park, 1930's. (Source: Public Places of Childhood, 1915-1930, Sanford Gaster)

With the pow-wows (where she met Crazy Bull, the grandson of Sitting Bull) they were grasping onto the culture, trying to be proud in their way. That moment was there for them before going back to welfare and their own neighborhood. It was their way of holding on.”

By 1938, Robert Moses, as part of his development plan for the park, evicted all of the residents, legal or illegal, of Inwood Hill. There were house-boaters, potters, squatters and of course Princess Naomi and her son Billy Kennedy, a featherweight boxer who helped build and paint fences in the park when he wasn’t in the ring. (His boxing record: won 19 (KO 3) + lost 28 (KO 10) + drawn 10 = 62)

Years later, Moses would say of the eviction process, which included chopping down what was left of the tulip tree: “There were other trees, many decrepit. In the middle was a kiln where an Indian princess taught ceramics under dubious auspices. She had a son who didn’t work. Both were on relief, and the relief checks were delivered to the princess at a mailbox fastened to a tree. The hullabaloo about disturbing the princess, the kiln, the old tulip tree, and other flora and fauna was terrific.” (Public Works, 1970).

Where Princess Naomi wound up after her unceremonious eviction in a mystery to this writer, but hopefully someone reading this article can help fill in those missing pieces.