During the 1920’s and 30’s an intrepid group of amphibious New Yorkers thumbed their noses at urban living, and high city rents, and took to dwelling in houseboat colonies along the perimeter of the Island of Manhattan.

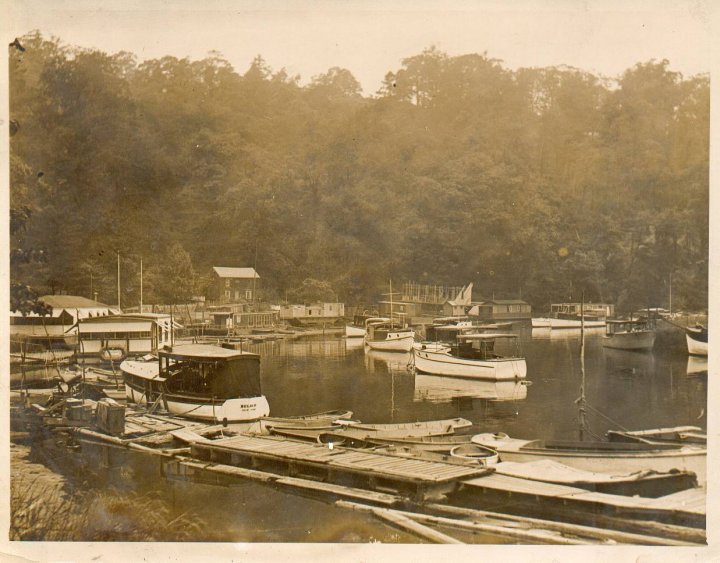

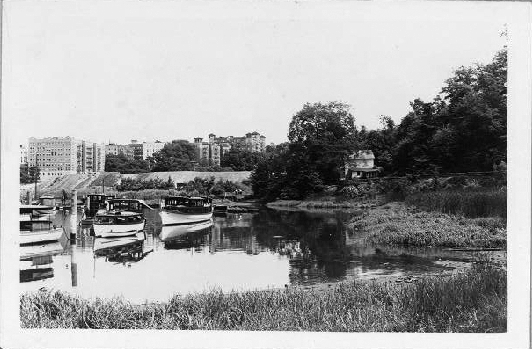

Two of those colonies, consisting of a ragtag group of artists, electricians and even police officers, were right here in Inwood. One was located on the shore of the Harlem River near 207th Street, while the other was in a boat basin once located at the foot of Inwood Hill along the Spuyten Duyvil.

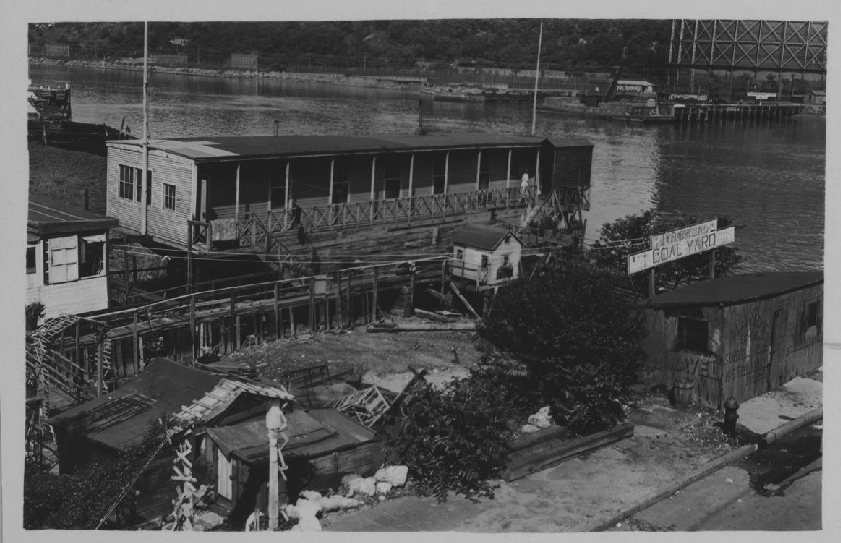

Like today, there was an east versus west of Broadway debate concerning who had the better digs. House-boaters east of Broadway, along the Harlem River, insisted they had better boats, hook-ups to electricity, city water and other public works as well as easy access to the local shopping district. Conversely, the Inwood Hill homesteaders, who lacked all modern amenities, including gas, water and electricity, considered their plot of shore, shaded by the famous Inwood Tulip, not far from the Inwood Pottery Works, to be the most tranquil and awe inspiring location in all of Manhattan.

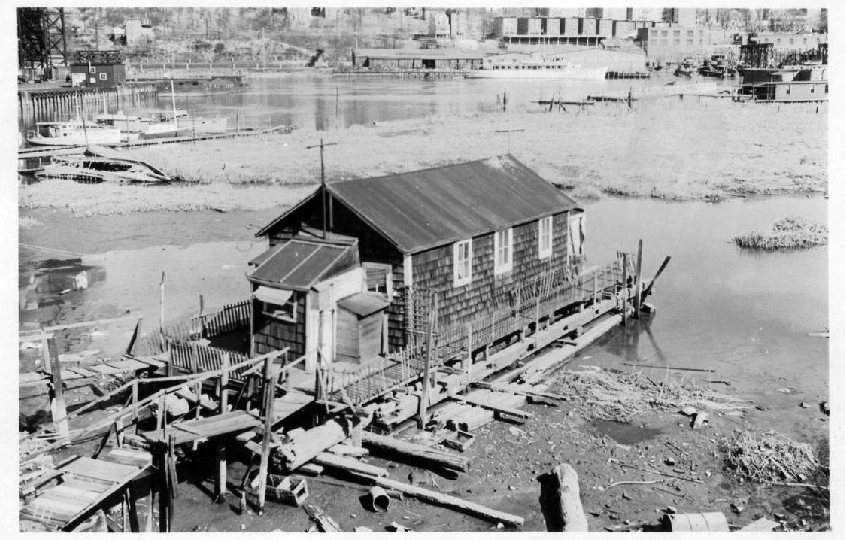

While some of the houseboats in both colonies were no longer seaworthy, their owners having long forsaken aquatic adventures, most were active sailing vessels whose owners lived for the summer months and life on the water. According to a May 24, 1923 account, published in the New York Evening Post which focused primarily on the Inwood Hill colony: “They seem to know that it will not be long before they will be able to forget the boredom of winter and slip away through Spuyten Duyvil into the broad Hudson, or down the Harlem for any one of a thousand places.

The land-bound houseboats, the half-and-halfs, and the floating ones are all alike, though, in feeling the meaning of the spring season. Most of them have already had fresh coats of paint; some are getting theirs now. They look as new as if they had never seen another spring, trim and neat as some old-time sailing craft just from the dry-dock and ready for her owner-master to sail her away across the seas.

Even if the houseboats do wander around five or six months out of the year they are more closely related to the house branch of their family tree than to the boat,” the article continued. Many had gardens, dogs and cats, and access to the old Cold Spring, a reliable source of pure ice cold water that once quenched the thirst of Lenape Indians who previously inhabited the region.

“Of course there are other houseboat colonies around Manhattan. There is a large one down the Harlem only a little way from Inwood with handsomer boats, perhaps, or more pretentious ones that are to be seen along the little cove, but what they lack is Inwood, a perfect background, majestic and colorful.”

What follows is a description of both Inwood houseboat colonies as seen through the eyes of Eleanor Booth Simmons, who, time and time again, turned her reporting to an Inwood that now exists in all but a few fading memories.

The Evening Post

July 10, 1920

By Eleanor Booth Simmons

It was a king of ancient times, wasn’t it, who could be healed grievous illness from which he suffered only by wearing the shirt of an absolutely happy man? And when his courtiers had scoured the land and found the happy man, he had no shirt. Well, I have seen a happy man, right here in Manhattan, and he had a shirt. He was wearing no collar when I met him, but that was merely because he didn’t want to be bothered. He pointed out that this was one reason he was happier than a millionaire; the millionaire had to “dress tight,” as he expressed it, while he could be loose and of comfortable attire.

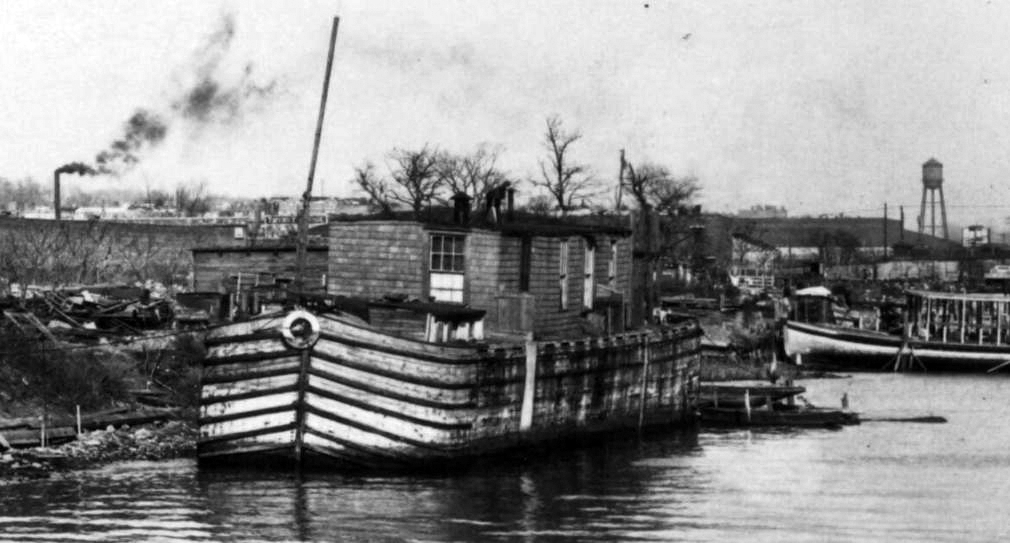

A happy man, you will say incredulously, here in Manhattan with the housing problem to contend with? That is the point. He has no housing problem. He beats the landlord by living all the year round in a houseboat, for the privilege of mooring which on the Harlem River he pays the city $60 a year.

And he has a garden to boot, stretching up the shore back of his boat, in which he raises all the vegetables consumed by his family of a wife and three sons and himself. There is food for the spirit here, too: and my happy man, albeit a cabinet-maker employed in a shop near his boat, has poetry in his soul. He was a seaman before he became a cabinet-maker, and absorbed something of the mystery of the deep.

“There’s nothing so secret as the sea in its ways,” he told me, “but nothing that will talk to you like the sea when you know it. The water talks to me at night when the comes up the Harlem, and this houseboat, that rests on land at low tide, rises and floats with the waves all around it. It has a pontoon bottom and floats like a steamship. It’s mighty pretty then, sitting here on the front deck like, and looking at the lights across the Harlem. Some folks may be coming along that bridge and looking down here will say, ‘What a poor little place!’ but I wouldn’t change with the happiest of them. I wouldn’t.”

Policemen Colony Members

His is not the only houseboat in this little sheltered nook on the Harlem, at 207th Street east of Tenth Avenue. At least fourteen of them are moored there, each with its little garden of flowers and vegetables , and each is occupied winter and summer. They have city water, gas and electricity, and their snug little coal-houses filled against the winter. My happy man assured me that there was never the shadow of trouble among them.

“There’s a policeman living in the boat next to mine,” he said, “and a police inspector in one of the others. But we never need ‘em though,” he added magnanimously; “we’re all good friends with ‘em.”

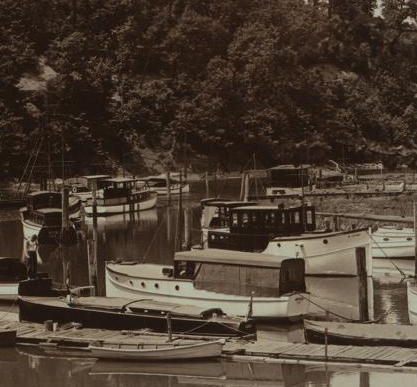

This is one of two houseboat colonies to be reached by 207th Street. The other may be termed the colony de luxe, for the boats are handsomer, there are some artists and such among the occupants, and the surroundings—the winding inlet of the old Spuyten Duyvil, and the vista of the Ship Canal in front, and the background of climbing cliffs hidden in splendid oaks and tulip trees—are as beautiful as could well be imagined. On the other hand, it is further away from the conveniences, and the house-boaters have to depend on kerosene for lighting or generate their own electricity. But they have the most delicious water in the world, cold and clear, from the springs that are everywhere in the cliffs above.

Finding the Happy Man

It was a hot, breathless Sunday when I started out in search of the houseboat colonies. From the Dyckman Street station of the Seventh Avenue subway I wandered north a little way, and found myself in a yard filled with Street Cleaning Department wagons, where two dogs with their foreheads wrinkled with responsibility to the city government made invidious remarks about me, and a good-natured man with a cat on his knees told me to keep on the right around the end of the bridge that spans the Harlem River at this point, and I’d find the houseboats. I did so, and there, looking at his corn and potatoes, with his wife and some visitors from downtown, was my happy man.

Further along the row of boats was Mr. Callahan, another old resident, who was cultivating the geraniums in his brilliant flowerbeds. In front of the boats the reeds, which at high tide are quite covered, waved in the slow breeze. There was a good smell of salt water and fish in the air. The inhabitants can cast their lines from their front porches and catch perch and other small fish, and clams are plentiful. Across the winding Harlem, a little way to the south, rose the buildings of New York University and the Hall of Fame, and all the opposite shore was beautiful with trees and stately red brick institutional buildings.

The happy man showed me through his houseboat and pointed out the various conveniences. The front room, opening off the porch, was a fair-sized sitting and dining room. Back of this were comfortable bedrooms, which were large enough to hold big beds and bureaus and so on and there was a bathroom with a good tub. A furnace heats the place in the winter, and I was told that even in the coldest weather it was snug as could be.

No More Houseboats Welcome

Its present owner paid $2,000 for this boat several years ago. Now, of course, it is worth more. They say there’s a long waiting list of people anxious to buy into the colony, but it’s a restricted suburb. The residents are determined not to be crowded, and they say there is no more room for any more boats. However, a couple of new boats are being built there now. It is the Dock Department to which one must apply for a permit to enter the colony, but, according to my happy man, he and his neighbors are dead set against anyone else coming in.

To reach the houseboats that lie below the Ship Canal I walked along 207th Street, across Broadway, to Seaman Avenue, followed the winding road up the hill and found four or five people working away around a little old house half hidden in the woods, carpentering and beating cushions, and a lady in a cretonne artist’s apron, Mrs. Alma (sic) Voorhees, came to answer my questions about where the houseboats were.

An active brown curly dog welcomed me at the first one, the Roanoke II, and its mistress, Mrs. May Waldis, who is a swimmer of note and has no end of cups and medals won in diving and swimming contests at Sheepshead Bay and the Sportsman’s Shows, and so on, took me inside and told me proudly how her husband had built every bit of the boat—and he is not a builder by trade, but an electrician. It is quite a palace of a boat, all brown and white outside, with Colonial-looking pillars, which are really water tanks.

Inside the walls are prettily paneled and the living room, the bedrooms and the kitchen and bathroom are as perfectly fitted up and as roomy as a nice apartment. And everywhere outside is the lapping water, and when Mrs. Waldis feels like a swim she can just dive of her front porch. Yet the Waldises are willing to sell this boat because Mr. Waldis, who is Virginia born, longs for the South again. Mrs. Waldis isn’t keen about parting with the snug little craft her husband built, but she is resigned. There is another fine houseboat there for sale—the “June”—for the owners, who are Swedes, want to go back to the old country.

Interested in reading more on life inside Inwood’s former houseboat colonies? Click here to read the story of Bill Isecke’s strange childhood growing up on the Harlem River near 207th Street during the late 1940s and mid-1950s – on a derelict cabin cruiser, berthed in a forgotten boatyard. This incredible oral history was collected by New York Wanderer Ben Feldman.